Number Theory Part-C

In this article we will cover the remaining and some advanced concepts of number theory.

Mathmatical Exceptation

Mathematical Expectation is an important concept in Probability Theory.This article attempts to throw some light on this topic by discussing few related mathematical and programming problems.

Mathematical expectation, also known as the expected value, which is the summation of all possible values from a random variable.It is also known as the product of the probability of an event occurring, denoted by P(x), and the value corresponding with the actually observed occurrence of the event. The mathematical expectation is denoted by the formula:

E(X)= Σ (x1p1, x2p2, …, xnpn)

It is important to understand that "expected value" is not same as "most probable value" - rather, it need not even be one of the probable values. For example, in a dice-throw experiment, the expected value, is not one of the possible outcomes at all.

The rule of "linearity of of the expectation" says that E[x1+x2] = E[x1] + E[x2].

Fermat's Theorem

It is also known as Fermat's little theorem. Fermat’s little theorem states that if p is a prime number, then for any integer a, the number a^(p) – a is an integer multiple of p.

Here p is a prime number ap ≡ a (mod p)

Let's see an Example How Fermat’s little theorem works

Examples:

P = an integer Prime number

a = an integer which is not multiple of P

Let a = 2 and P = 17

According to Fermat's little theorem

2^(17 - 1) ≡ 1 mod(17)

we got 65536 % 17 ≡ 1

that mean (65536-1) is an multiple of 17

// Java program to find modular

// inverse of a under modulo m

// using Fermat's little theorem.

// This program works only if m is prime.

class Main {

static int __gcd(int a, int b) {

if (b == 0) {

return a;

} else {

return __gcd(b, a % b);

}

}

// To compute x^y under modulo m

static int power(int x, int y, int m) {

if (y == 0) {

return 1;

}

int p = power(x, y / 2, m) % m;

p = (p * p) % m;

return (y % 2 == 0) ? p : (x * p) % m;

}

// Function to find modular

// inverse of a under modulo m

// Assumption: m is prime

static void modInverse(int a, int m) {

if (__gcd(a, m) != 1) {

System.out.print("Inverse doesn't exist");

} else {

// If a and m are relatively prime, then

// modulo inverse is a^(m-2) mode m

System.out.print("Modular multiplicative inverse is " + power(a, m - 2, m));

}

}

// Driver code

public static void main(String[] args) {

int a = 3, m = 11;

modInverse(a, m);

}

}Wilson's Theorem

Wilson’s theorem states that a natural number p > 1 is a prime number if and only if

(p-1) ! ≡ -1 mod p

OR (p-1) ! ≡ (p-1) mod p

Examples:

p = 5 (p-1)! = 24 24 % 5 = 4

p = 7 (p-1)! = 6! = 720 720 % 7 = 6

Proof: It is easy to check the result when n is 2 or 3, so let us assume n > 3. If n is composite, then its positive divisors are among the integers 1, 2, 3, 4, ... , n-1 and it is clear that gcd( (n-1)! , n) > 1, so we can not have (n-1)! = -1 (mod n).

However if n is prime, then each of the above integers are relatively prime to n. So for each of these integers a there is another b such that ab = 1 (mod n). It is important to note that this b is unique modulo n, and that since n is prime, a = b if and only if a is 1 or n-1. Now if we omit 1 and n-1, then the others can be grouped into pairs whose product is one showing

2.3.4.....(n-2) = 1 (mod n)

(or more simply (n-2)! = 1 (mod n)). Finally, multiply this equality by n-1 to complete the proof.

Lucas Theorem

Lucas theorem basically suggests that the value of nCr can be computed by multiplying results of niCri where ni and ri are individual same-positioned digits in base p representations of n and r respectively.. The idea is to one by one compute niCri for individual digits ni and ri in base p.Since these digits are in base p, we would never need more than O(p) space and time complexity of these individual computations would be bounded by O(p2).

// A Lucas Theorem based solution to compute nCr % p

class Lucas {

// Returns nCr % p. In this Lucas Theorem based program,

// this function is only called for n < p and r < p.

static int nCrModpDP(int n, int r, int p) {

// The array C is going to store last row of

// pascal triangle at the end. And last entry

// of last row is nCr

int[] C = new int[r + 1];

C[0] = 1; // Top row of Pascal Triangle

// One by constructs remaining rows of Pascal

// Triangle from top to bottom

for (int i = 1; i <= n; i++) {

// Fill entries of current row using previous

// row values

for (int j = Math.min(i, r); j > 0; j--)

// nCj = (n-1)Cj + (n-1)C(j-1);

C[j] = (C[j] + C[j - 1]) % p;

}

return C[r];

}

// Lucas Theorem based function that returns nCr % p

// This function works like decimal to binary conversion

// recursive function. First we compute last digits of

// n and r in base p, then recur for remaining digits

static int nCrModpLucas(int n, int r, int p) {

// Base case

if (r == 0) {

return 1;

}

// Compute last digits of n and r in base p

int ni = n % p;

int ri = r % p;

// Compute result for last digits computed above, and

// for remaining digits. Multiply the two results and

// compute the result of multiplication in modulo p.

return (nCrModpLucas(n / p, r / p, p) * // Last digits of n and r

nCrModpDP(ni, ri, p)) % p; // Remaining digits

}

// Driver program

public static void main(String[] args) {

int n = 1000, r = 900, p = 13;

System.out.println("Value of nCr % p is " + nCrModpLucas(n, r, p));

}

}Chinese Remainder Theorem

Chinese Remainder Theorem states that there always exists an x that satisfies given congruences.

Let num[0], num[1], …num[k-1] be positive integers that are pairwise coprime. Then, for any given sequence of integers rem[0], rem[1], … rem[k-1], there exists an integer x solving the following system of simultaneous congruences. A Naive Approach to find x is to start with 1 and one by one increment it and check if dividing it with given elements in num[] produces corresponding remainders in rem[]. Once we find such an x, we return it.

// A Java program to demonstrate the working of Chinese remainder theorem

class ChineseRemainderTheorem {

// k is size of num[] and rem[]. Returns the smallest

// number x such that:

// x % num[0] = rem[0],

// x % num[1] = rem[1],

// ..................

// x % num[k-2] = rem[k-1]

// Assumption: Numbers in num[] are pairwise coprime

// (gcd for every pair is 1)

static int findMinX(int num[], int rem[], int k) {

int x = 1; // Initialize result

// As per the Chinese remainder theorem,

// this loop will always break.

while (true) {

// Check if remainder of x % num[j] is

// rem[j] or not (for all j from 0 to k-1)

int j;

for (j = 0; j < k; j++)

if (x % num[j] != rem[j]) {

break;

}

// If all remainders matched, we found x

if (j == k) {

return x;

}

// Else try next number

x++;

}

}

// Driver method

public static void main(String args[]) {

int num[] = { 3, 4, 5 };

int rem[] = { 2, 3, 1 };

int k = num.length;

System.out.println("x is " + findMinX(num, rem, k));

}

}NP-Completeness

A problem is in the class NPC if it is in NP and is as hard as any problem in NP. A problem is NP-hard if all problems in NP are polynomial time reducible to it, even though it may not be in NP itself.

NP-Hard If a polynomial time algorithm exists for any of these problems, all problems in NP would be polynomial time solvable. These problems are called NP-complete. The phenomenon of NP-completeness is important for both theoretical and practical reasons.

Definition of NP-Completeness

A language B is NP-complete if it satisfies two conditions:

- B is in NP.

- Every A in NP is polynomial time reducible to B.

If a language satisfies the second property, but not necessarily the first one, the language B is known as NP-Hard. Informally, a search problem B is NP-Hard if there exists some NP-Complete problem A that Turing reduces to B.

The problem in NP-Hard cannot be solved in polynomial time, until P = NP. If a problem is proved to be NPC, there is no need to waste time on trying to find an efficient algorithm for it. Instead, we can focus on design approximation algorithm.

NP-Completeness Problems:

Following are some NP-Complete problems, for which no polynomial time algorithm is known.

- Determining whether a graph has a Hamiltonian cycle

- Determining whether a Boolean formula is satisfiable, etc.

**NP-Hard Problems

The following problems are NP-Hard

- The circuit-satisfiability problem

- Set Cover

- Vertex Cover

- Travelling Salesman Problem

In this context, now we will discuss TSP is NP-Complete:

TSP is NP-Complete

The traveling salesman problem consists of a salesman and a set of cities. The salesman has to visit each one of the cities starting from a certain one and returning to the same city. The challenge of the problem is that the traveling salesman wants to minimize the total length of the trip

Okay so let's move to some more advanced concepts:

1. Bit Masking + Dynamic Programming

First thing to make sure before using bitmasks for solving a problem is that it must be having small constraints, as solutions which use bitmasking generally take up exponential time and memory.

Let's first try to understand what Bitmask means. Mask in Bitmask means hiding something. Bitmask is nothing but a binary number that represents something. Let's take an example. Consider the set A={1,2,3,4,5}. We can represent any subset of A using a bitmask of length 5, with an assumption that if ith(0<=i<=4) bit is set then it means ith element is present in subset. So the bitmask 01010 represents the subset {2,4}

Now the benefit of using bitmask. We can set the ith bit, unset the ith bit, check if ith bit is set in just one step each. Let's say the bitmask b = 01010.

Set the ith bit : b|(1<<i). Let i = 0, so,

(1<<i) = 00001 01010 | 00001 = 01011

So now the subset includes the 0th element also, the subset is {1,2,4}.

Unset the ith bit : b&!(1<<i). Let i = 1, so

(1<<i) = 00010

!(1<<i) = 11101

00010 & 11101 = 01000

Now the subset does not include the 1st element so the subset now is {4}.

Checking if the ith bit is set: b&(1<<i) doing this operation if ith bit is set we will get a non-zero integer other wise a zero.

Let i =3,

(1<<i) = 01000

01010 & 01000 = 01000

Clearly the result is non-zero so that means 3rd element is present in the subset.

Lets take a problem where given a set we have to count how many subsets have sum of elements greater than or equal to a give value.

Algorithm is simple:

solve(set, set_size, val)

count = 0

for x = 0 to power(2, set_size)

sum = 0

for k = 0 to set_size

if kth bit is set in x

sum = sum + set[k]

if sum >= val

count = count + 1

return countTo iterate over all the subsets we are going to each number from 0 to 2^(set_size)-1. The above problem simply uses bitmask and complexity is O(N2^(N)).

Assignment Problem:

There are N persons and N tasks, each task is to be alloted to a single person. We are also given a matrix cost of size NxN , where cost[i][j] denotes, how much person i is going to charge for task j. Now we need to assign each task to a person in such a way that the total cost is minimum. Note that each task is to be alloted to a single person, and each person will be alloted only one task.

The brute force approach here is to try every possible assignment. Algorithm is given below:

assign(N, cost)

for i = 0 to N

assignment[i] = i //assigning task i to person i

res = INFINITY

for j = 0 to factorial(N)

total_cost = 0

for i = 0 to N

total_cost = total_cost + cost[i][assignment[i]]

res = min(res, total_cost)

generate_next_greater_permutation(assignment)

return resThe complexity of above algorithm is O(N!), well that's clearly not good.

Let's try to improve it using dynamic programming. Suppose the state of dp is (k,mask) , where k represents that person 0 to k-1 have been assigned a task, and mask is a binary number, whose ith bit represents if the ith task has been assigned or not. Now, suppose, we have answer(k,mask), we can assign a task i to person k, iff ith task is not yet assigned to any peron i.e. mask&(i<<i) = 0 then answer(k+1,mask|(1<<i)), will be given as:

answer(k+1,mask|(1<<i)) = min(answer(k+1,mask|(1<<i)), answer(k,mask)+cost[k][i])

One thing to note here is k is always equal to the number set bits in mask , so we can remove that. So the dp state now is just (mask), and if we have answer(mask), then

answer(mask|(1<<i)) = min(answer(mask|(1<<i)), answer(mask)+cost[x][j])

here x = number of set bits in mask. Complete algorithm is given below:

assign(N, cost)

for i = 0 to power(2,N)

dp[i] = INFINITY

dp[0] = 0

for mask = 0 to power(2, N)

x = count_set_bits(mask)

for j = 0 to N

if jth bit is not set in i

dp[mask|(1<<j)] = min(dp[mask|(1<<j)], dp[mask]+cost[x][j])

return dp[power(2,N)-1]

Time complexity of above algorithm is O(N*2^N) and space complexity is O(2^N). This is just one problem that can be solved using DP+bitmasking. There's a whole lot.

2. Extended Euclidean Algorithm

While the Euclidean algorithm calculates only the greatest common divisor (GCD) of two integers a and b, the extended version also finds a way to represent GCD in terms of a and b, i.e. coefficients x and y for which:

ax+by=gcd(a,b)

It's important to note, that we can always find such a representation, for instance, gcd(55,80)=5 therefore we can represent 5 as a linear combination with the terms 55 and 80, 55x3+80x(−2)=5.

Algorithm

We will denote the GCD of a and b with g in this section.

The changes to the original algorithm are very simple. If we recall the algorithm, we can see that the algorithm ends with b=0 and a=g. For these parameters, we can easily find coefficients, namely gx1+0x0=g.

Starting from these coefficients (x,y)=(1,0), we can go backwards up the recursive calls. All we need to do is to figure out how the coefficients x and y change during the transition from (a,b) to (b, a mod b).

Let us assume we found the coefficients (x1,y1) for (b,amodb):

b⋅x1+(amodb)⋅y1=g

and we want to find the pair (x,y) for (a,b):

a⋅x+b⋅y=g

We can represent amodb as:

amodb=a−⌊a/b⌋⋅b

Substituting this expression in the coefficient equation of (x1,y1) gives:

g=b⋅x1+(amodb)⋅y1=b⋅x1+(a−⌊a/b⌋⋅b)⋅y1

and after rearranging the terms:

g=a⋅y1+b⋅(x1−y1⋅⌊a/b⌋)

We found the values of x and y:

x=y1

y=x1−y1⋅⌊a/b⌋

Implementation

class Extended {

// extended Euclidean Algorithm

public static int gcdExtended(int a, int b, int x, int y)

{

// Base Case

if (a == 0) {

x = 0;

y = 1;

return b;

}

int x1 = 1, y1 = 1; // To store results of recursive call

int gcd = gcdExtended(b % a, a, x1, y1);

// Update x and y using results of recursive

// call

x = y1 - (b / a) * x1;

y = x1;

return gcd;

}

// Driver Program

public static void main(String[] args)

{

int x = 1, y = 1;

int a = 35, b = 15;

int g = gcdExtended(a, b, x, y);

System.out.print("gcd(" + a + ", " + b + ") = " + g);

}

}

3. Modulo Multiplicative Inverse

In modular arithmetic we do not have a division operation. However, we do have modular inverses.

- The modular inverse of A (mod C) is A^-1

- (A * A^-1) ≡ 1 (mod C) or equivalently (A * A^-1) mod C = 1

- Only the numbers coprime to C (numbers that share no prime factors with C) have a modular inverse (mod C)

Example: A=3, C=7

- 3 * 0 ≡ 0 (mod 7)

- 3 * 1 ≡ 3 (mod 7)

- 3 * 2 ≡ 6 (mod 7)

- 3 * 3 ≡ 9 ≡ 2 (mod 7)

- 3 * 4 ≡ 12 ≡ 5 (mod 7)

- 3 * 5 ≡ 15 (mod 7) ≡ 1 (mod 7) <------ FOUND INVERSE!

- 3 * 6 ≡ 18 (mod 7) ≡ 4 (mod 7)

Implementation -1 (Naive)

A Naive method is to try all numbers from 1 to m. For every number x, check if (a*x)%m is 1.

Time Complexity: O(m).

class Modulo{

static int modInverse(int a, int m)

{

for (int x = 1; x < m; x++)

if (((a%m) * (x%m)) % m == 1)

return x;

return 1;

}

public static void main(String args[])

{

int a = 3, m = 11;

// Function call

System.out.println(modInverse(a, m));

}

}

Implementation -2 (Extended Euler’s GCD algorithm - Iterative)

The idea is to use Extended Euclidean algorithms that takes two integers ‘a’ and ‘b’, finds their gcd and also find ‘x’ and ‘y’ such that

ax + by = gcd(a, b)

Time Complexity: O(Log m)

class Modulo{

// Returns modulo inverse of a with

// respect to m using extended Euclid

// Algorithm Assumption: a and m are

// coprimes, i.e., gcd(a, m) = 1

static int modInverse(int a, int m)

{

int m0 = m;

int y = 0, x = 1;

if (m == 1)

return 0;

while (a > 1) {

// q is quotient

int q = a / m;

int t = m;

// m is remainder now, process

// same as Euclid's algo

m = a % m;

a = t;

t = y;

// Update x and y

y = x - q * y;

x = t;

}

// Make x positive

if (x < 0)

x += m0;

return x;

}

// Driver code

public static void main(String args[])

{

int a = 3, m = 11;

// Function call

System.out.println("Modular multiplicative "

+ "inverse is "

+ modInverse(a, m));

}

}

Implementation-3 (Works when m is prime)

If we know m is prime, then we can also use Fermats’s little theorem to find the inverse.

am-1 ≅ 1 (mod m)

Time Complexity: O(Log m)

class Modulo{

// Function to find modular inverse of a

// under modulo m Assumption: m is prime

static void modInverse(int a, int m)

{

int g = gcd(a, m);

if (g != 1)

System.out.println("Inverse doesn't exist");

else

{

// If a and m are relatively prime, then modulo

// inverse is a^(m-2) mode m

System.out.println(

"Modular multiplicative inverse is "

+ power(a, m - 2, m));

}

}

static int power(int x, int y, int m)

{

if (y == 0)

return 1;

int p = power(x, y / 2, m) % m;

p = (int)((p * (long)p) % m);

if (y % 2 == 0)

return p;

else

return (int)((x * (long)p) % m);

}

// Function to return gcd of a and b

static int gcd(int a, int b)

{

if (a == 0)

return b;

return gcd(b % a, a);

}

// Driver Code

public static void main(String args[])

{

int a = 3, m = 11;

// Function call

modInverse(a, m);

}

}4. Linear Diophantine Equations

A Diophantine equation is a polynomial equation, usually in two or more unknowns, such that only the integral solutions are required. An Integral solution is a solution such that all the unknown variables take only integer values. Given three integers a, b, c representing a linear equation of the form : ax + by = c. Determine if the equation has a solution such that x and y are both integral values.

Input : a = 3, b = 6, c = 9

Output: Possible

Explanation : The Equation turns out to be,

3x + 6y = 9 one integral solution would be

x = 1 , y = 1

Input : a = 3, b = 6, c = 8

Output : Not Possible

Explanation : o integral values of x and y

exists that can satisfy the equation 3x + 6y = 8

Input : a = 2, b = 5, c = 1

Output : Possible

Explanation : Various integral solutions

possible are, (-2,1) , (3,-1) etc.

Solution:

For linear Diophantine equation equations, integral solutions exist if and only if, the GCD of coefficients of the two variables divides the constant term perfectly. In other words the integral solution exists if, GCD(a ,b) divides c. Thus the algorithm to determine if an equation has integral solution is pretty straightforward.

- Find GCD of a and b

- Check if c % GCD(a ,b) ==0

- If yes then print Possible

- Else print Not Possible

Below is the implementation of above approach.

class Equation {

// Utility function to find the GCD

// of two numbers

static int gcd(int a, int b)

{

return (a % b == 0) ?

Math.abs(b) : gcd(b,a%b);

}

// This function checks if integral

// solutions are possible

static boolean isPossible(int a, int b, int c)

{

return (c % gcd(a, b) == 0);

}

// Driver function

public static void main (String[] args)

{

// First example

int a = 3, b = 6, c = 9;

if(isPossible(a, b, c))

System.out.println( "Possible" );

else

System.out.println( "Not Possible");

// Second example

a = 3; b = 6; c = 8;

if(isPossible(a, b, c))

System.out.println( "Possible") ;

else

System.out.println( "Not Possible");

// Third example

a = 2; b = 5; c = 1;

if(isPossible(a, b, c))

System.out.println( "Possible" );

else

System.out.println( "Not Possible");

}

} Output :

Possible

Not Possible

Possible5. Matrix Exponentiation

The concept of matrix exponentiation in its most general form is very useful in solving questions that involve calculating the nth term of a linear recurrence relation in time of the order of log(n).

For solving the matrix exponentiation we are assuming a

linear recurrence equation like below:

F(n) = a*F(n-1) + b*F(n-2) + c*F(n-3) for n >= 3

. . . . . Equation (1)

where a, b and c are constants.

For this recurrence relation, it depends on three previous values.

Now we will try to represent Equation (1) in terms of the matrix.

[First Matrix] = [Second matrix] * [Third Matrix]

| F(n) | = Matrix 'C' * | F(n-1) |

| F(n-1) | | F(n-2) |

| F(n-2) | | F(n-3) |

Dimension of the first matrix is 3 x 1 .

Dimension of the third matrix is also 3 x 1.

So the dimension of the second matrix must be 3 x 3

[For multiplication rule to be satisfied.]

Now we need to fill the Matrix 'C'.

So according to our equation.

F(n) = a*F(n-1) + b*F(n-2) + c*F(n-3)

F(n-1) = F(n-1)

F(n-2) = F(n-2)

C = [a b c

1 0 0

0 1 0]

Now the relation between matrix becomes :

[First Matrix] [Second matrix] [Third Matrix]

| F(n) | = | a b c | * | F(n-1) |

| F(n-1) | | 1 0 0 | | F(n-2) |

| F(n-2) | | 0 1 0 | | F(n-3) |

Lets assume the initial values for this case :-

F(0) = 0

F(1) = 1

F(2) = 1

So, we need to get F(n) in terms of these values.

So, for n = 3 Equation (1) changes to

| F(3) | = | a b c | * | F(2) |

| F(2) | | 1 0 0 | | F(1) |

| F(1) | | 0 1 0 | | F(0) |

Now similarly for n = 4

| F(4) | = | a b c | * | F(3) |

| F(3) | | 1 0 0 | | F(2) |

| F(2) | | 0 1 0 | | F(1) |

- - - - 2 times - - -

| F(4) | = | a b c | * | a b c | * | F(2) |

| F(3) | | 1 0 0 | | 1 0 0 | | F(1) |

| F(2) | | 0 1 0 | | 0 1 0 | | F(0) |

So for n, the Equation (1) changes to

- - - - - - - - n -2 times - - - - -

| F(n) | = | a b c | * | a b c | * ... * | a b c | * | F(2) |

| F(n-1) | | 1 0 0 | | 1 0 0 | | 1 0 0 | | F(1) |

| F(n-2) | | 0 1 0 | | 0 1 0 | | 0 1 0 | | F(0) |

| F(n) | = [ | a b c | ] ^ (n-2) * | F(2) |

| F(n-1) | [ | 1 0 0 | ] | F(1) |

| F(n-2) | [ | 0 1 0 | ] | F(0) |

So we can simply multiply our Second matrix n-2 times and then multiply it with the third matrix to get the result. Multiplication can be done in (log n) time using Divide and Conquer algorithm for power. Let us consider the problem of finding n’th term of a series defined using below recurrence.

n'th term,

F(n) = F(n-1) + F(n-2) + F(n-3), n >= 3

Base Cases :

F(0) = 0, F(1) = 1, F(2) = 1We can find n’th term using following :

| F(n) | = [ | 1 1 1 | ] ^ (n-2) * | F(2) |

| F(n-1) | [ | 1 0 0 | ] | F(1) |

| F(n-2) | [ | 0 1 0 | ] | F(0) |Java Implementation

Time Complexity: O(logN) Auxiliary Space: O(logN)

// JAVA program to find value of f(n) where

// f(n) is defined as

// F(n) = F(n-1) + F(n-2) + F(n-3), n >= 3

// Base Cases :

// F(0) = 0, F(1) = 1, F(2) = 1

class Matrix {

// A utility function to multiply two

// matrices a[][] and b[][].

// Multiplication result is

// stored back in b[][]

static void multiply(int a[][], int b[][])

{

// Creating an auxiliary matrix to

// store elements of the

// multiplication matrix

int mul[][] = new int[3][3];

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

{

for (int j = 0; j < 3; j++)

{

mul[i][j] = 0;

for (int k = 0; k < 3; k++)

mul[i][j] += a[i][k]

* b[k][j];

}

}

// storing the multiplication

// result in a[][]

for (int i=0; i<3; i++)

for (int j=0; j<3; j++)

// Updating our matrix

a[i][j] = mul[i][j];

}

// Function to compute F raise to

// power n-2.

static int power(int F[][], int n)

{

int M[][] = {{1, 1, 1}, {1, 0, 0},

{0, 1, 0}};

// Multiply it with initial values

// i.e with F(0) = 0, F(1) = 1,

// F(2) = 1

if (n == 1)

return F[0][0] + F[0][1];

power(F, n / 2);

multiply(F, F);

if (n%2 != 0)

multiply(F, M);

// Multiply it with initial values

// i.e with F(0) = 0, F(1) = 1,

// F(2) = 1

return F[0][0] + F[0][1] ;

}

// Return n'th term of a series defined

// using below recurrence relation.

// f(n) is defined as

// f(n) = f(n-1) + f(n-2) + f(n-3), n>=3

// Base Cases :

// f(0) = 0, f(1) = 1, f(2) = 1

static int findNthTerm(int n)

{

int F[][] = {{1, 1, 1}, {1, 0, 0},

{0, 1, 0}} ;

return power(F, n-2);

}

// Driver code

public static void main (String[] args) {

int n = 5;

System.out.println("F(5) is "

+ findNthTerm(n));

}

}

//This code is contributed by vt_m.

6. Combinatorics

Combinatorial mathematics, the field of mathematics concerned with problems of selection, arrangement, and operation within a finite or discrete system. Included is the closely related area of combinatorial geometry.

One of the basic problems of combinatorics is to determine the number of possible configurations (e.g., graphs, designs, arrays) of a given type. Even when the rules specifying the configuration are relatively simple, enumeration may sometimes present formidable difficulties. The mathematician may have to be content with finding an approximate answer or at least a good lower and upper bound.

In mathematics, generally, an entity is said to “exist” if a mathematical example satisfies the abstract properties that define the entity. In this sense it may not be apparent that even a single configuration with certain specified properties exists. This situation gives rise to problems of existence and construction. There is again an important class of theorems that guarantee the existence of certain choices under appropriate hypotheses. Besides their intrinsic interest, these theorems may be used as existence theorems in various combinatorial problems.

Here we will be discussing a few problems that can be implemented using the concepts of Combinatorics

Generating Permutations

A permutation is an act of rearranging a sequence in such a way that it has a different order.

As we know from math, for a sequence of n elements, there are n! different permutations. n! is known as a factorial operation:

n! = 1 * 2 * … * nAlgorithm

It's a good idea to think about generating permutations in a recursive manner. Let's introduce the idea of the state. It will consist of two things: the current permutation and the index of the currently processed element.

The only work to do in such a state is to swap the element with every remaining one and perform a transition to a state with the modified sequence and the index increased by one.

Let's illustrate with an example.

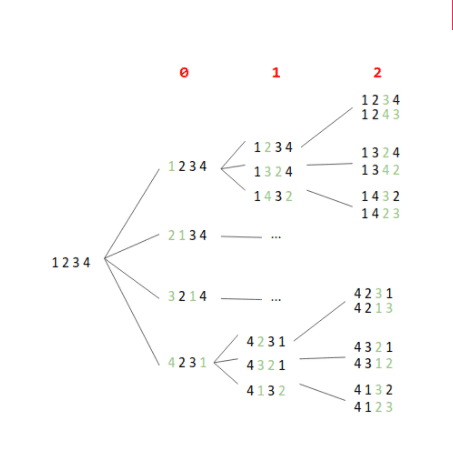

We want to generate all permutations for a sequence of four elements – [1, 2, 3, 4]. So, there will be 24 permutations. The illustration below presents the partial steps of the algorithm:

Each node of the tree can be understood as a state. The red digits across the top indicate the index of the currently processed element. The green digits in the nodes illustrate swaps.

So, we start in the state [1, 2, 3, 4] with an index equal to zero. We swap the first element with each element – including the first, which swaps nothing – and move on to the next state.

Java Impelementation

private static void permutationsInternal(List<Integer> sequence, List<List<Integer>> results, int index) {

if (index == sequence.size() - 1) {

permutations.add(new ArrayList<>(sequence));

}

for (int i = index; i < sequence.size(); i++) {

swap(sequence, i, index);

permutationsInternal(sequence, permutations, index + 1);

swap(sequence, i, index);

}

}Generating the Powerset of a Set

Powerset (or power set) of set S is the set of all subsets of S including the empty set and S itself

So, for example, given a set [a, b, c], the powerset contains eight subsets:

[]

[a]

[b]

[c]

[a, b]

[a, c]

[b, c]

[a, b, c]Java Implementation

private static void powersetInternal(

List<Character> set, List<List<Character>> powerset, List<Character> accumulator, int index) {

if (index == set.size()) {

results.add(new ArrayList<>(accumulator));

} else {

accumulator.add(set.get(index));

powerSetInternal(set, powerset, accumulator, index + 1);

accumulator.remove(accumulator.size() - 1);

powerSetInternal(set, powerset, accumulator, index + 1);

}

}Generating Combinations

Now, it's time to tackle combinations. We define it as follows:

k-combination of a set S is a subset of k distinct elements from S, where an order of items doesn't matter

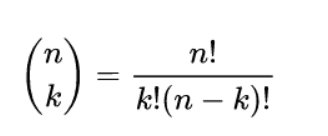

The number of k-combinations is described by the binomial coefficient:

So, for example, for the set [a, b, c] we have three 2-combinations:

[a, b]

[a, c]

[b, c]Java Implementation

private static void combinationsInternal(

List<Integer> inputSet, int k, List<List<Integer>> results, ArrayList<Integer> accumulator, int index) {

int needToAccumulate = k - accumulator.size();

int canAcculumate = inputSet.size() - index;

if (accumulator.size() == k) {

results.add(new ArrayList<>(accumulator));

} else if (needToAccumulate <= canAcculumate) {

combinationsInternal(inputSet, k, results, accumulator, index + 1);

accumulator.add(inputSet.get(index));

combinationsInternal(inputSet, k, results, accumulator, index + 1);

accumulator.remove(accumulator.size() - 1);

}

}